Why We Need More Nature, and How to Make it Fun

Author and journalist Richard Louv grew up in Missouri and Kansas, and spent much of his childhood playing “in the woods at the edge of our housing development with my dog.”

To date, Louv has authored nine books, was the keynote speaker at the first White House Summit on Environmental Education in 2012, and is responsible for starting a worldwide movement to reconnect families—and specifically children—back to nature. A father of two, Louv also co-founded the Children & Nature Network, a resource for parents, teachers and others looking to connect to nature. His most recent book, “Vitamin N,” is also a resource for living a “nature-rich life.”

24Life asked Louv to share how nature affects humans, what we’re missing out on by not spending more time in nature and how parents can make nature time more fun for kids.

24Life: What is nature-deficit disorder and how is it impacting us?

RL: “Nature-deficit disorder” is not a medical diagnosis, but a useful term—a metaphor—to describe what many of us believe are the human costs of alienation from nature, as suggested by recent research. Among them: diminished use of the senses, attention difficulties, higher rates of physical and emotional illnesses, a rising rate of myopia, child and adult obesity, vitamin D deficiency and other maladies.

24Life: From a science-based perspective, what does spending more time in nature do to our brains and bodies?

RL: The research indicates that experiences in the natural world appear to offer great psychological and physical health benefits, and the ability to learn, for children and adults. Direct and indirect contact with nature can help with recovery from mental fatigue and the restoration of attention, as well as help restore the brain’s ability to think. Nature is an antidote to stress—children, parents, just about everyone feels better after spending time in the natural world. Researchers in Sweden have found that joggers who exercise in natural green settings feel more restored and less anxious, angry or depressed.

Time spent in nature is obviously not a cure-all, but it can be an enormous help, especially for kids and adults who are stressed by circumstances beyond their control. The studies strongly suggest that time in nature can help many children learn to build confidence in themselves, reduce the symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, calm them and help them focus. Schools with natural play spaces and nature learning areas appear to help children do better academically. There are some indications that natural play spaces can also reduce bullying, and nature experience can also be a buffer to child obesity. Nature experience also helps grow conservation values, now and in the future.

There are many other benefits, and more supportive research comes out almost weekly. The Children & Nature Network website has compiled a large body of studies, reports and publications that are available for viewing or downloading.

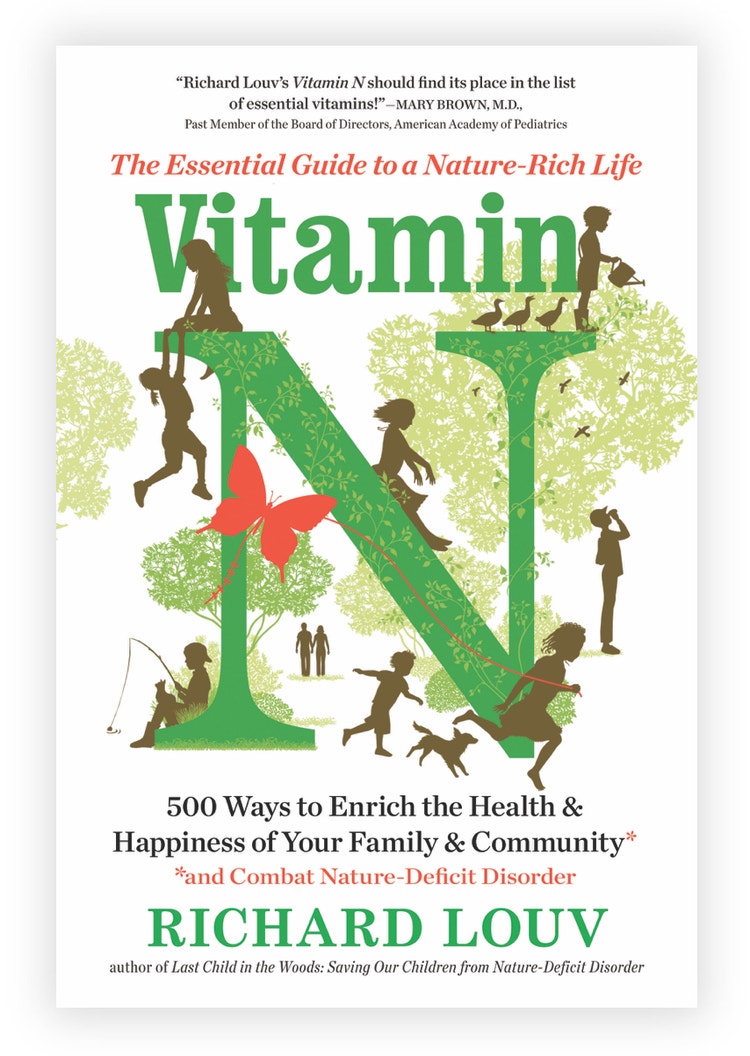

24Life: What inspired you to write “Vitamin N”?

RL: We’re at a crucial point in what I call the new nature movement. Awareness has grown over the past decade, but we need to move more quickly into an action mode, whether we’re parents, pediatricians or mayors. That need is a big part of my motivation for writing “Vitamin N” (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, April 2016), which includes 500 actions that people can take to enrich the health and happiness of their families and communities.

“Vitamin N” is useful not only to parents, but to grandparents, teachers, pediatricians, mayors, young adults and single people, too. It helps folks move from awareness to action.

24Lfie: What have we missed out on by becoming more technologically dependent than nature-dependent?

RL: The more high-tech our lives become, the more nature we need. I’m not against technology in education, or in our lives, but we do need balance—and time spent in the natural world, whether nearby urban nature or wilderness, provides that.

The ultimate multitasking is to live simultaneously in both the digital and the physical world, using computers to maximize our powers to process intellectual data, and natural environments to ignite all of our senses and accelerate our ability to learn and to feel; in this way, we would combine the resurfaced “primitive” powers of our ancestors with the digital speed of our teenagers. Today, people who work and learn in a digital-dominant environment expend enormous energy blocking out many of the human senses—including ones we don’t even know we have—in order to focus narrowly on the screen in front of the eyes. That’s the very definition of being less alive. What parent wants their child to be less alive? Who among us wants to be less alive?

24Life: How do you like to spend time in nature? How have you seen it change your life?

RL: With my wife, Kathy, I’ve raised two boys. Our backyard is San Diego County, where we spend as much time hiking in the mountains and desert as we can, and fishing on the bay and out on the Pacific and in the lakes dotted through the backcountry. This is one of the most biologically diverse regions in the United States.

I find it difficult to pull away from screens, just as so many others do. When my boys were small, my wife and I had perhaps more motivation to leave the computers and the house and to be in nature, and take our sons with us so that they could experience nature. Now she and I must create that motivation only for ourselves. So recently we have consciously been going on what I call techno-fasts: Leaving the electronics and heading for the mountains for a few days. There are many other ways my family connects to nature, and I try to do it even when I’m traveling and speaking, and even in the most urban places.

Make nature fun

“If children are given the opportunity to experience nature, even in simple ways, interaction and engagement follow quite naturally,” says Louv. But parents should not push too hard, as time out in nature should never be seen as a punishment for spending too much time in front of the TV, he warns.

Rather, Louv advises leading by example. “When parents rediscover their sense of wonder, so do most kids.”

Here are a few ideas Louv suggests:

- Discover a hidden universe. Find a scrap board and place it on bare dirt. Come back in a day or two, lift the board, and see how many species have found shelter there. Identify these creatures with the help of a field guide. Return to this universe once a month, lift the board and discover who’s new. (First, learn about venomous spiders and snakes that might come to visit.)

- Be a cloudspotter. No special shoes or drive to the soccer field is required for clouding. A young person just needs a view of the sky (even if it’s from a bedroom window) and a guidebook. To build a backyard weather station, read “The Kid’s Book of Weather Forecasting,” by Mark Breen, Kathleen Friestad and Michael Kline.

- Pick a “sit spot.” Be a wildwatcher. Jon Young, preeminent nature educator and co-author of “Coyote’s Guide,” advises children and adults to find a special place, whether it’s under a tree at the end of the yard, a hidden bend of a creek or a rooftop garden. “Know the birds that live there, know the trees they live in. Get to know these things as if they were your relatives … That is the most important thing you can do in order to excel at any skill in nature.”

- Purchase a family park pass. National parks, national monuments and some wildlife refuges and regional parks exist in urban as well as wilderness areas. Many parks charge for admission, but as Forbes magazine points out, they aren’t a bad deal when compared to other forms of recreation: “Going to a movie for a family of four can cost around $80. Bowling for four for two hours on a Saturday can cost around $90, not including food.” In comparison, an unlimited annual family pass to the national parks costs $80; it’s free for members of the military and those with permanent disabilities. (Beginning in September 2015, all fourth graders in the United States—and their families—became eligible for a free annual pass to the national parks and other federal natural lands through the program, Every Kid in a Park.)

- Enroll your child in a nature preschool or other nature-based school. Encourage Natural Teachers. Work with your PTA to honor them with awards. Help plant a garden or natural play space at your child’s school.

- Teenagers: Get wild. Extreme outdoor sports like rock-climbing are one way to get your teens outside. They can also volunteer to do outdoor service projects, or discover outdoor careers.

Richard Louv is co-founder and chairman emeritus of the Children & Nature Networkand author of “The Nature Principle: Reconnecting with Life in a Virtual Age ” and “ Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder.” His most recent book is, “ Vitamin N: The Essential Guide to a Nature-Rich Life.” He is currently working on his tenth book, about the evolving relationship between humans and other animals.

Photo credit: Alex Holyoake, Unsplash; Courtesy of Richard Louv