What is the Interstitium and Why Should We Care About it?

Last week, scientists claimed discovery of a “new” organ: the interstitium. The recently published study has created quite a bit of buzz in the health and fitness world, and rightly so, given so many experts contribute to a growing body of work regarding our human anatomy and physiology. But what is the interstitium, and is it really a “new” discovery?

We asked a few experts—self-care expert and founder of Tune Up Fitness, Jill Miller; biomechanist and founder of Nutritious Movement, Katy Bowman; Institute of Motion founder, Michol Dalcourt; and physical therapist and MobilityWOD founder, Kelly Starrett—to share a little background on this long-overlooked organ, and why the recent publicity matters.

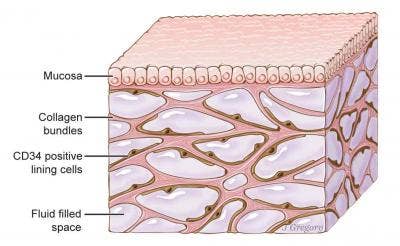

A newfound organ, the interstitium, is seen here beneath the top layer of skin, but is also in tissue layers lining the gut, lungs, blood vessels, and muscles. The organ is a body-wide network of interconnected, fluid-filled compartments supported by a meshwork of strong, flexible proteins.

What is the interstitium?

Jill Miller: The interstitium is the fluid-filled and membranous zone of fascial tissues that creates a transition zone between the fatty layer (superficial) and deep fascia (tougher fascia surrounding muscles). This zone can also be found within muscles and surrounding organs.

Is it really new? Why was it just “discovered”?

Miller: This zone has been explained by multiple fascia researchers in the past two decades including Gil Hedley, Thomas Myers, J.C. Guimberteau and more. New imaging techniques are clarifying this structure and allowing new researchers to clearly see the fluid pathways within fascia as never before. Formerly, when studied under a microscope, the fluids would have been expelled and the fibrous fascial components were flattened and thus couldn’t reveal the complexity of its in vivo arrangement. Now with confocal laser microscopy new vistas within our body can be clearly seen and hopefully understood.

Kelly Starrett: The way to think about it is, “Ah, look; (now) we have a model for understanding movements and tissue health. This reinforces what we know and the way we’re all practicing already.”

We know that myofascial release has been around for a long time. We know that there are certain positions in yoga that correspond very well with some of the meridians of fascial tensegrity (which holds our anatomy in place). What’s amazing is if you go back to even the oldest self-care modalities like gua sha, you understand that people have been feeling how the body moves under our hands for as long as there have been people.

What we’re understanding, too, is that the Western model—I’m a classically trained Western physical therapist—talks about muscles and bones because those were things that were easy to see. But if you actually look at early anatomist drawings, you’ll see that they’re describing these fascial trains because they were doing them in the wet dissection.

What we don’t recognize is that maybe we’re doing even more than we thought (for healing) because we’re able to circulate lymph and we’re able to circulate aspects of your immune system that we didn’t even realize we were. We may not be getting one bang for the buck, we may be getting three bangs for the buck.

Why is it such a big “discovery”?

Miller: Your body is 78 percent fluid, most of it contained in your fascial tissues and in zones like the interstitium. The fluids circulate throughout your body like a slow moving estuary and your movement practice, nutrition, environment, emotional health and sleep all contribute to the chemistry of this internal river system. Your lymphatic system draws fluids and disease fighting cells from this area and your muscle cells also eliminate into it. It is a dynamic barrier that is a first line of defense in protecting your structures, like an internal life vest. The study enthusiastically describes how the fluids within this zone may be helpful in understand how cancer cells may roam from one region of the body to another.

Michol Dalcourt: These pockets may prove critical to shock absorption, the fight against disease and cellular motility.

Why the heated debate over whether or not the interstitium is real or an organ?

Katy Bowman: We’re in a time where we utilize scientific findings as beacons for behavior. It’s important to understand that science changes over time and if you use science in this way, understanding how the process works is beneficial.

As I read on the debates around this, I see arguments on how the interstitium cannot be an organ as it’s not continuous with all its parts. I immediately think of watersheds. Is my watershed in Washington state “connected” to the watershed in Detroit? Does my behavior influence my water and the water of others? I think you could argue that my habits of driving, consuming (what I eat, how much plastic I use, etc.) actually do connect me to water outside where I can see and touch.

So how one defines “connected” can influence if you feel this abundant “thing” called the interstitium matters or if it doesn’t. What this paper does is sort of force people to consider it. Someone has said “this is a thing and maybe it matters” and while peer-review doesn’t mean everyone agrees, it means that it’s observable enough to the point that it begs consideration. So, it matters because people going forward will add it to their models of “important things in the body.”

How can we take care of our interstitium?

Dalcourt: Good physical, nutritional and sleep hygiene will do a lot for: healthy collagen and elastin (fibers found in this fluid-filled space), extracellular matrix motility (through mechanotranduction), hydration (which could have benefits to this fluid-filled space), and good regulation of cell production and signaling.

Photo credit: fizkes, Thinkstock; Illustration by Jill Gregory. Printed with permission from Mount Sinai Health System, licensed under CC-BY-ND.