Seeing More Dimensions – In Color, and Life

Alexa Meade redefined her course and makes us see double in her art.

Park on a desolate side street off the Los Angeles River and on the edge of LA’s Chinatown district, where light industry, importers and warehouses are distinguishable from one another only by shades of grimy white and gray. Enter an opening in one building’s sheet-metal wall, and pause until your eyes adjust to the cavernous darkness.

There’s an open set of double doors up ahead, and you turn the corner to step into a painted world that brightens from deep rosy to peach and salmon hues. To your right, lively yellow and green strokes bring to life a vanity that might just up and walk away.

That’s how Alexa Meade brings her subjects to life — what they are and what they could be —as the walls of her studio progress to shades of purple-blue through rich emerald tones evoking foliage to an impressionistic bookcase with a world globe enrobed in a complex paint maze of brushstrokes distinguishes contours and countries.

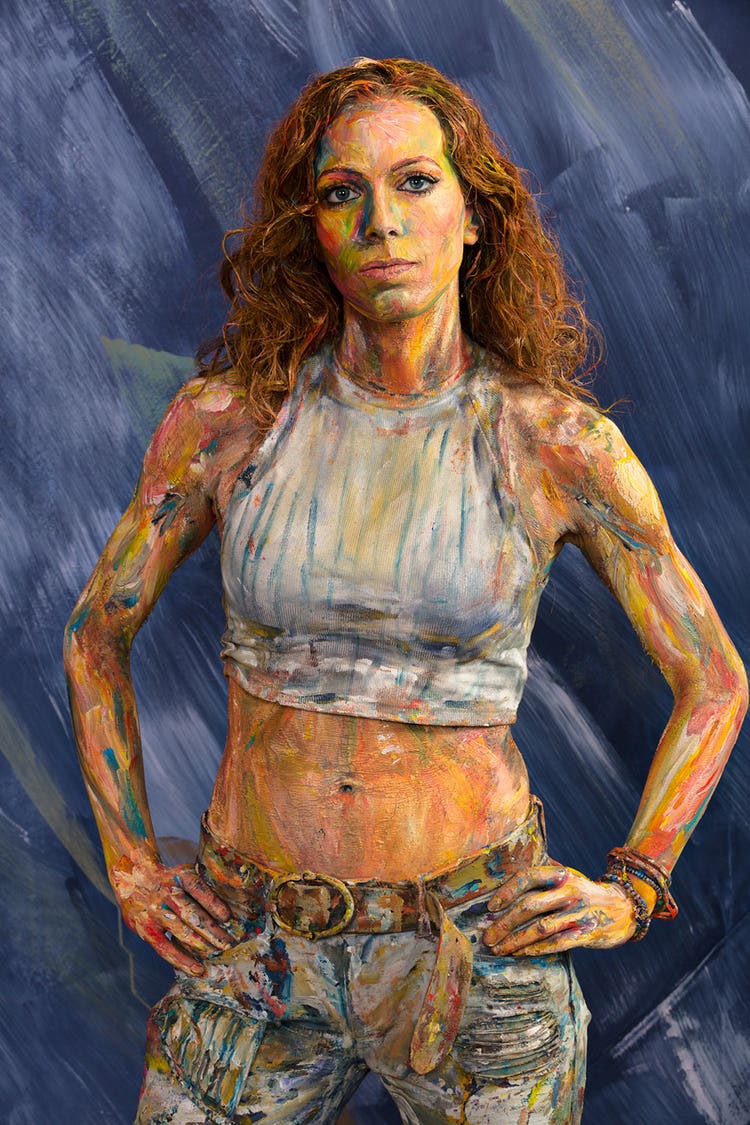

Meade is at her studio, preparing to create the cover for the first edition of 24Life in 2017: a self-portrait.

Her history — and making her story

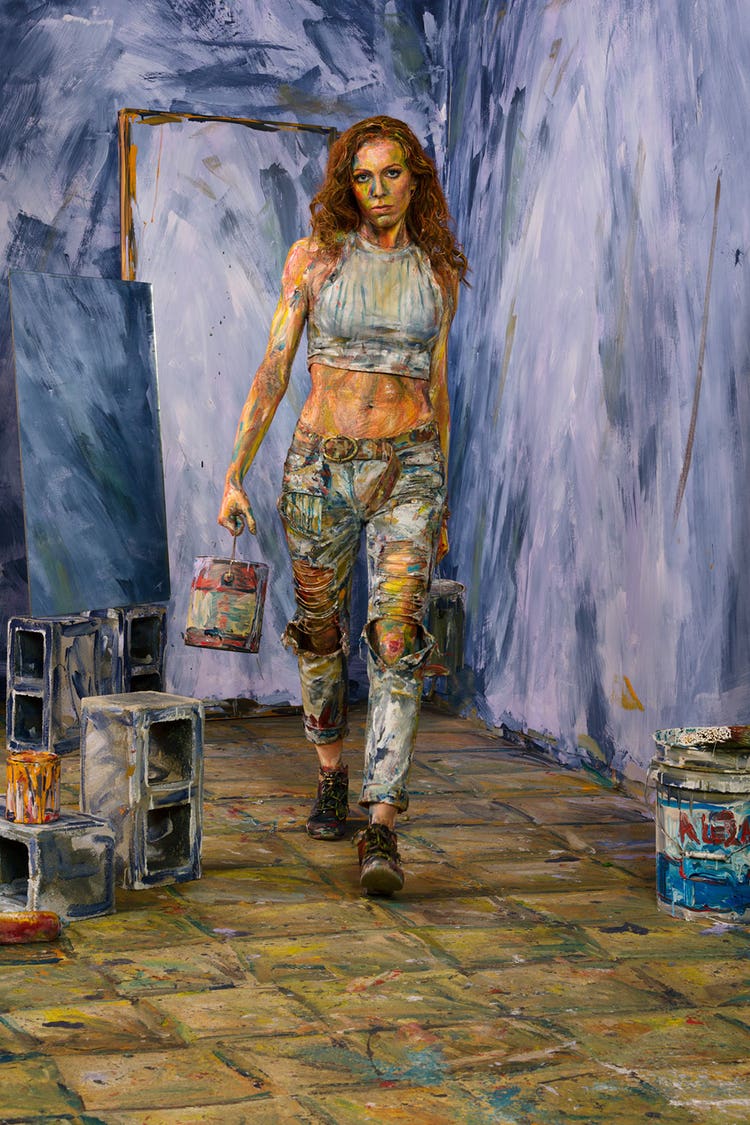

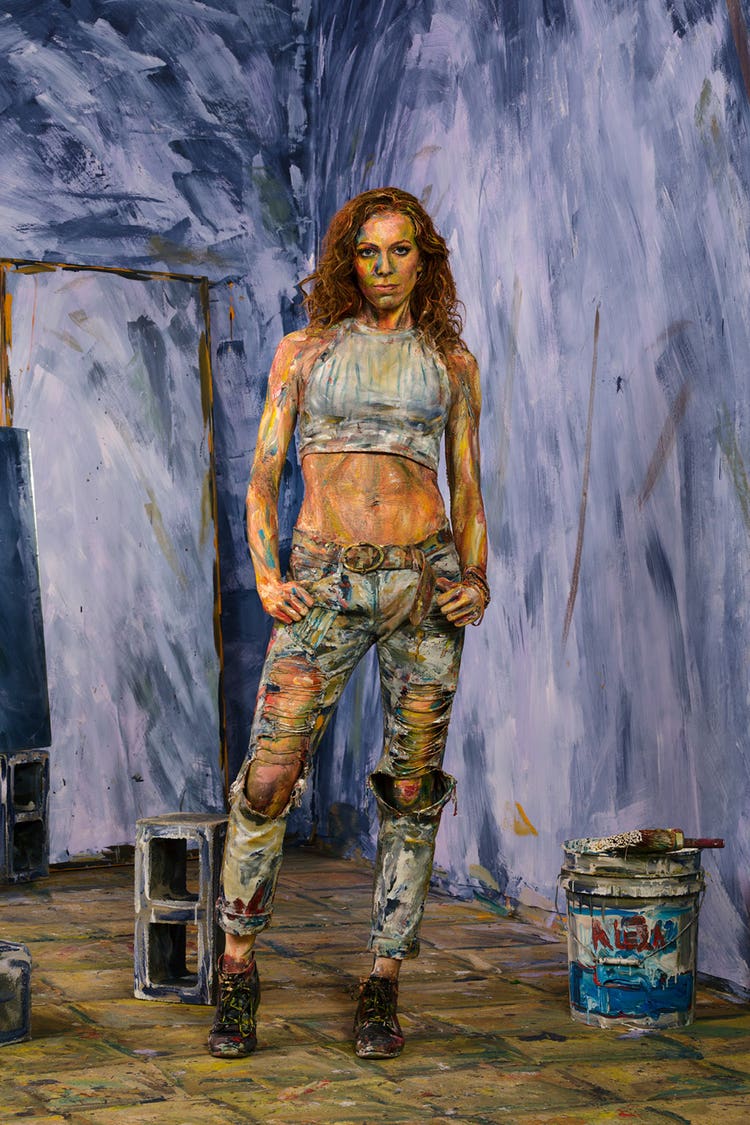

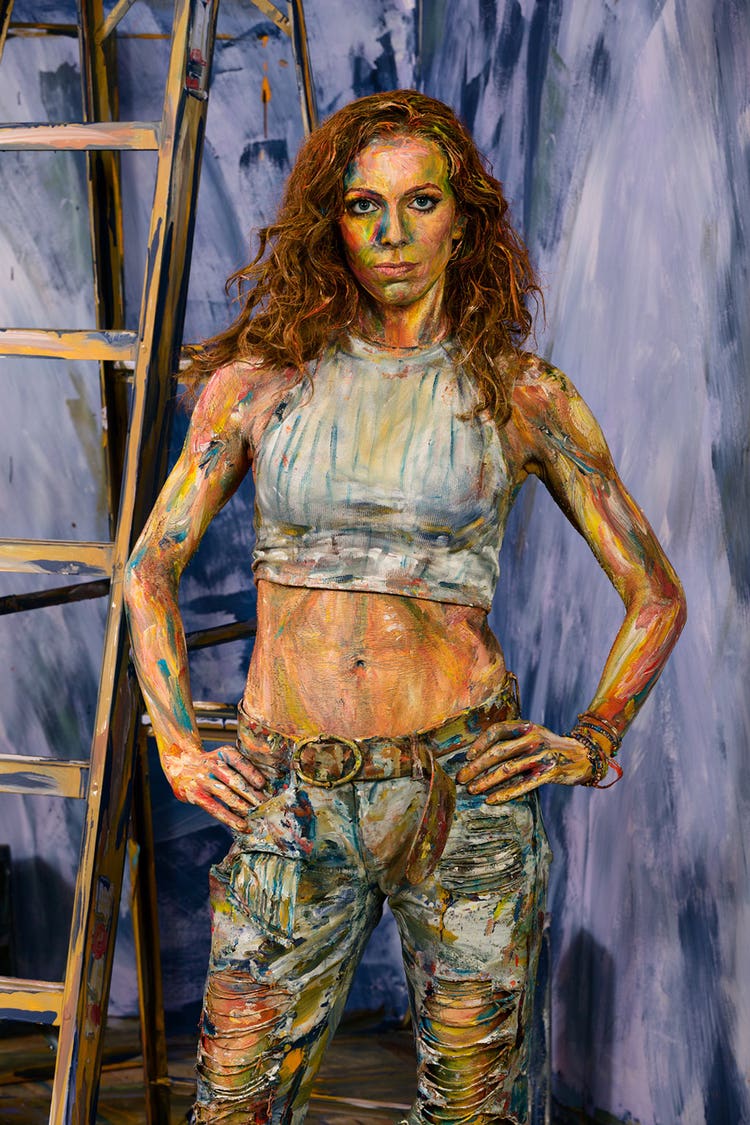

Meade begins her work with a blank canvas of sorts; in this case, large sheets of clean white paper cover two walls, and Meade looks fresh in a white cutoff tank, torn jeans, and beat-up belt and boots. The sheer physicality of her work lifting, reaching and bending to paint her subjects keeps her lean and toned, and as she begins to explain her process, she flexes and jokes that her painting arm’s bigger. (It is, a little.)

Meade didn’t plan to be an artist. Growing up in Washington, D.C., Meade says she laid out a “super-neat path” for herself: “I interned on Capitol Hill for four summers, and then I worked on probably a half-dozen campaigns, and studied political science, and I went to Europe to study the European Union.”

But something wasn’t right. “I just felt like even though this was supposed to be my dream, it didn’t quite fit with who I thought I was on the inside,” she says.

Meade’s sharp turn in her story came from something deeper, an urge that was sparked in an elective art class in college. “The professor asked us to create a sculpture that felt like a landscape but was not a sculpture of a landscape. I had no idea what that meant, and I kept asking for clarification, and he told me it was up to me to figure out.”

She thought about capturing a landscape through its shadows rather than objects themselves. “I came up with this idea of putting black paint on the ground where the shadows were,” she says. (Her professor didn’t like her initial project proposal, but she’s quick to credit him as a subsequent mentor in the ways that she thinks about space, light and shadow.)

Thus began her fascination. “I decided to see what it would look like if I put black shadows on the human body,” she says. “And then painting not only shadows but also a full mapping of light in grayscale, highlights, darks, everything coming together in a mask of paint. Just by creating a mask of [shadow and] light with paint, it completely transformed the space. After I discovered this, I think I just had to leave politics behind and make my job teaching myself how to paint, through the process of inventing this new style of painting.”

Meade could make people and things look like two-dimensional paintings of themselves. She abruptly stepped off her path to politics, moved back home and set out on a new journey. “It felt like an incredible risk because I had been building up my entire life to this one moment of making my debut and having a real job, as my parents called it,” she says. “And instead of getting a real job, I decided to make my job painting on grapefruits, and eggs, and things you’re not meant to put paint on. It didn’t really seem like it was a career path, but it felt like something I just had to do.”

That drive in me was so strong that there was really no point in fighting it,” she adds, “because it would have won out eventually.”

The mind-boggling effect of crossing back and forth between 2-D and 3-D, which happens when you see her work in progress (or when you see it move), is something that has captivated audiences beyond the realm of the art world, from quantum physicists to technologists and even political scientists. Her people and objects exist in 2-D and 3-D states, simultaneously, which is why experts in these disciplines have turned to Meade’s work to illustrate theoretical phenomena.

Making life out of light and shadow

Meade now looks at the world and sees things differently. “I sometimes mix up 2-D and 3-D, when I look at paintings in two dimensions,” she acknowledges. “I oftentimes see it as a three-dimensional space …[because] my brain keeps on flipping it around to make everything have depth hidden behind it.”

Meade also sees light and shadow as a nuance of color. “I start breaking everything up into colors,” she explains, “especially within shadows, seeing, OK, it’s a mixture of green and purple together, and I don’t quite know the name for that color, but I know that’s something that I have to capture.” Meade finds her mind’s eye has been opened, as well. It’s in the effort to paint those spaces in between named colors that she says, “I find myself more open to just being surprised and embracing the feelings of magic, the unknown.”

As she turns her attention to painting her boots and jeans, the effect is not immediately apparent, and then suddenly it is. On first glance, white paint — and light blue, and red, and yellow — is streaked on her pants and daubed on her boots. Then, suddenly, the colors resolve into something else, something hyper-real. The jeans come to life, and so do the boots. When you look at a photo of her work in progress, your eye does not distinguish the untouched parts of Meade, and you take it all in as a painted representation rather than a photograph of a real woman with paint on her body.

Her vision is mentally and physically demanding to execute, requiring Meade to paint live, pinning down light and shadows as they actually exist. Her work can include the undersides of tables and the insides of books and drawers that may never be opened. That’s because she is completing a world and painting not only what is but also what she sees. Painting on clothing must be done while the subject is wearing it: “I have to understand that the creases all mean something,” she says. “They’re depicting something about the underlying bone structure and body. If I get the drapery wrong, then all of a sudden I could drastically misrepresent the person who’s underneath it.”

Painting on people reveals even greater sensitivity and awareness of her subjects through Meade’s process. “When I paint on people, it’s different from painting on canvas,” she explains. “Because each person has a story within them, many stories. I take photos from different angles, and I might have a certain view of what the final image will be, but it’s the life that comes out of the person that really brings the artwork to life.”

She paints both what appears to be and what she sees within her subject. It resonates with complete strangers, such as the woman who told Meade that she saw in one portrait her own haggard face and body — and the spark in the woman’s living, unpainted eye. It prompted the viewer to leave an abusive relationship, and it continues to inspire her to become the woman that she is inside.

Making a practice of making mistakes and seeking the unknown

Of course, Meade can’t make the life in the eyes of the person she’s painted. The uncertainty is where she has focused her attention and where she finds meaning. “All the time while I’m painting, there will be these little mini-crises that pop up and I have to problem-solve on my feet,” she says. “One of the things is that when I start painting, I can’t stop. I can’t tell the model to come back tomorrow,” because the work is created live. She says so much improvisation is required that “it’s oftentimes when I can’t get that thing that I want that I get something that’s absolutely ineffable, beyond description, and beyond what I could have imagined.”

Now she embraces the unpredictability, starting a story and following that story wherever it takes her, at the same time. “Whenever I set out to paint something and I have a very clear vision in my head of what it’s supposed to look like and then I match that, it’s absolutely disappointing,” she says. “That’s what I’m constantly seeking —to find that thing that I do not know.”

Seeking out the unknown has led Meade to new challenges. In a collaboration with Sheila Vand, Meade painted on Vand, who would then lie down in a pool of milk. The perfection of her work might dissolve in some instances or completely transform the image in others. “There was so much about letting go of that complete control over what could happen and adding that element of the unknown, of allowing this thing that was beautiful that I want to hold onto forever, to just completely dissolve and melt away because it’s in that process of transformation that the real living and life happens,” she says.

From her radical departure from a path toward politics, Meade now sees her job as taking risks in order to bring the unknown to light. “What I’m constantly seeking in my art is to create these opportunities where there’s no choice but to take a risk. I have to commit to it and see it through,” she says. “Part of the role of the artist is to put things out there that other people can’t see.”

Finished with her self-creation for the magazine, the photography begins. Despite the fact that the photographer and everyone present in the room have witnessed the process, the sense is one of watching a mythical figure come to life. Only when she happens to move too close to a light on the set is the illusion broken.

“Art tells a story. It can’t help but do that,” Meade says. “When you create something that has a certain amount of ambiguity built into it, people come at it with their own perceptions, their own point of view, and see something that might not have been intended by the artist but that speaks to them in a way that feels like it can’t help but be there. We make our own stories; we make our own meanings from the things around us.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nXEnUvbyJQ0

Photography: Tom Casey, Box24Studio.com

Hair and make-up: Akua Auset, Akua-Auset.com