Getting Tight With the Integumentary System

As humans, we’re born with skin that is arguably the world’s most beautiful surface. A baby’s nose and cheeks (and arms! and toes!) are softer and lovelier than delicate rose petals or silky puppy ears.

Of course, the texture of our skin changes as we grow, but we never develop the hard shell of a tortoise or the tough hide of an elephant. For the most part, our skin stays pretty soft. In fact, we’re constantly being reminded by advertisers and health authorities how delicate our skin is. We need the right soap, or cream, or sunblock to keep it functioning. After all, you can cut it with a piece of paper!

With such a fragile outer coating, isn’t it curious that we’ve made it to the top of the food chain? Compared to an armadillo, we look like tender, vulnerable lion food.

But, in truth, skin is no wimp. It’s the largest organ in the body, making up roughly 15 percent of our total body weight. It creates a strong, flexible, waterproof barrier between the wide world and our warm and squishy insides. Skin, and the associated structures that make up our integumentary system, do a seriously tough job of protecting us.

Integu-what?

The integumentary system. Also referred to as the integument, it is the biological system made up of our skin, hair, nails and other things like sweat glands and interstitial fluid. Let’s break it down a little.

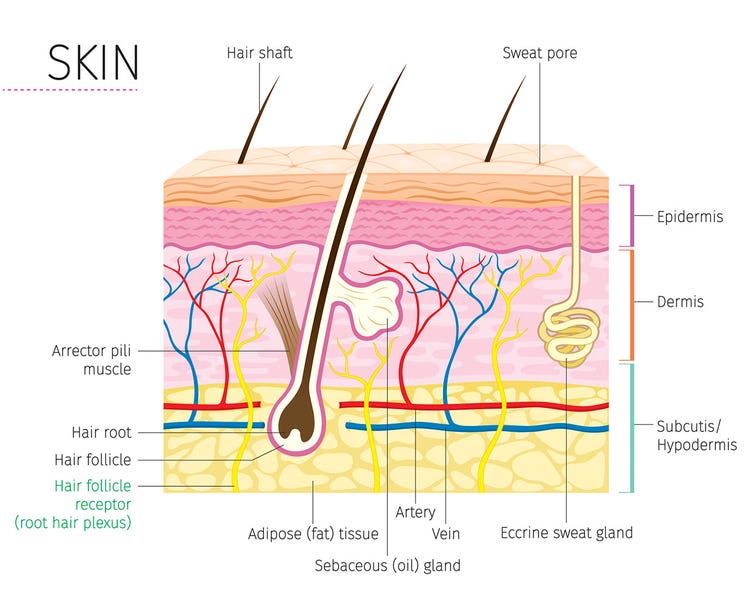

Skin: Made up of two distinct layers, the epidermis and the dermis.

Epidermis: This is a relatively thin layer of epithelial cells that absorb oxygen directly from the air (a vital characteristic, given the epidermis doesn’t have any blood vessels in it). Most of the epidermis is waterproof thanks to the presence of a fibrous protein called keratin, which is also the main component of hair and nails.

Dermis: This thicker layer sits beneath the epidermis and is filled with connective tissue formed by various arrangements of collagen and elastin proteins. This tissue provides dynamic support that makes the skin stretchy and flexible but also resistant to deformation or wrinkling. The dermis contains blood vessels, sweat glands, hair follicles, interstitial fluid and sensory receptors.

Hypodermis: Also called the subcutaneous layer, the hypodermis primarily consists of a layer of fat storage that provides quickly accessible energy to the bloodstream. It also acts as insulation, helping us maintain an optimal body temperature.

Interstitium: You may have heard about this recent discovery of fluid-filled pockets within connective and other tissues. Though there is some debate as to whether it is a “new” observation, we do know that the interstitial fluid surrounds many types of cells within the body—including in the dermal and hypodermal tissues of the integumentary system.

Real-time data and regulation

Just like the screen and buttons on your phone allow you to use it without damaging its electronic guts, our integumentary system is how we safely interface with our environment. It serves many functions for the body—from making vitamin D to controlling evaporation. These include three key protections:

1. Protects homeostasis

Homeostasis is our body’s happy place—the balance of temperature, processes and energy reserves our body works to return to after managing a stressful event (good or bad). The integument helps to restore homeostasis by storing lipid and water molecules to provide energy and hydration when needed. Sweat glands in the dermis allow heat to escape via pores in the epidermis, and the dermal blood vessels can dilate to help expel even more heat. When we get chilly, goose bumps lift up our body hair, insulating us by trapping warm air close to the skin.

2. Who goes there?

Our skin contains many free nerve endings that send the brain information about temperature, pain and our basic sense of touch. Interestingly, the nerve endings that sense heat are located deeper in the tissue layers than those that sense cold, meaning we’re faster at detecting cold than heat. Who knew?

Skin also contains specialized nerve cells called mechanoreceptors that are highly sensitive to external mechanical (touch) stimuli and can even sense weak stimuli, such as when someone is almost-but-not-quite touching you.

3. Taking the hits

Sure, the skin is our first line of defense against water loss and germ invasion, but it also helps mediate the physical impact of living in the world. Exercise and other daily activities mean walking on hard floors, running on concrete sidewalks, bumping into door jambs on our way to the coffee maker in the morning and—everyone’s favorite—toe stubbing. And while our skin can’t take away the pain of a toe stubbing, it does help spread out the force of the bump so the toe doesn’t break. The elastic connective tissue and fluid-filled spaces of the dermis, interstitium and deeper structures help cushion our bones and distribute forces. When we walk, for example, the skin, connective tissue, muscles and joints in our feet spread outward to absorb the impact of our step. This prevents our foot bones from shattering and saves ankle and knee joints from excessive wear and tear.

Healthy skin tips

Dermatology books and blogs have got the market cornered on clinical ways to improve skin, from creams and injections to lights and lasers. But if you’re interested in a more DIY approach to healthy skin and aging, these two tips might be more your thing.

Circulate and hydrate: OK, so this is usually No. 1 on the dermatologist’s list, too, but drinking water is only half the equation. We also have to move the water into the places it needs to go. Remember the fluid-filled pockets of the interstitium? It, like the rest of our connective tissue, works like a sponge, losing water when squeezed and refilling with water when relaxed. Interval training and high-intensity interval training workouts can create this squeezing action. The high intensity squeezes the active areas like a sponge, while the rest periods let it rehydrate with fresh fluid. Exercises that move from the ground to a standing position also push fluid around the body using the pumping action of our muscles.

Mechanical stress: Moving is very beneficial for skin, thanks to a process called mechanotransduction. It’s a big word, I know, but is a fairly simple concept. Mechanotransduction is when mechanical stress creates cellular activity. One of these activities is remodeling. As we stretch our skin through movement, it triggers connective tissue cells to line up along the direction of the stretch and begin to produce collagen (among other things) along that line of stress. Increasing the amount of collagen in the skin makes it stronger and tighter. Although it can’t reverse sun damage, a 2014 study found that the skin of sedentary seniors (aged 65 and up) who began an aerobic exercise program became more healthy and elastic, like the skin of 20- to 40-year-olds.

Photo credit: nd3000, Thinkstock; MatoomMi, Thinkstock; JadeThaiCatwalk, Thinkstock; Wendy Hope, Thinkstock